USC Cardiac and Vascular Institute surgeons discuss how they saved an aortic dissection patient using smart collaboration and a trial device.

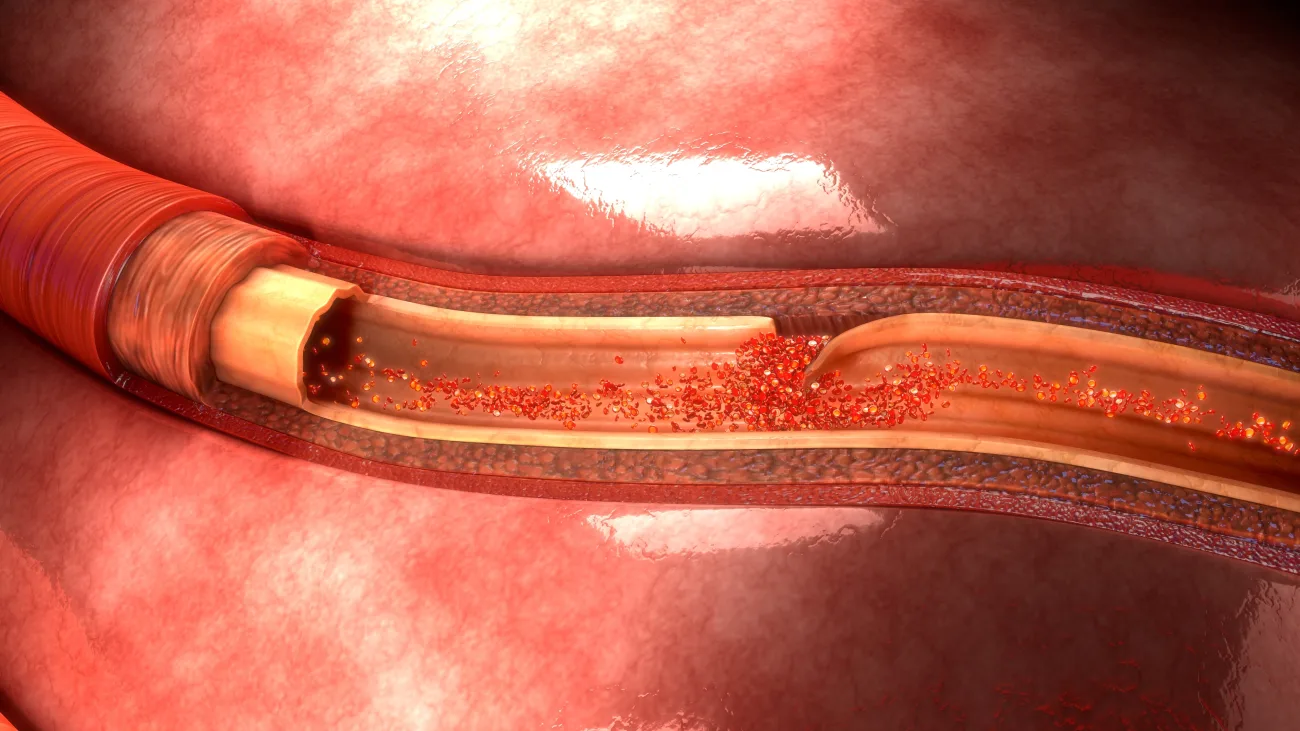

Once an aortic dissection happens, the clock is ticking — especially if malperfusion occurs.

“Malperfusion significantly increases mortality risk after an aortic dissection,” explains Sukgu M. Han, MD, a vascular surgeon at the USC Cardiac and Vascular Institute, part of Keck Medicine of USC. “Even if the patient survives after surgeons fix the aorta, blood flow usually can’t be restored quickly enough to the organs, and the patient goes into multi-organ failure.”

Often, it takes a team of experts to pull a patient back from the brink of danger. In May 2023, specialists at the USC Cardiac and Vascular Institute worked together to find a unique solution to treat a 46-year-old male in Los Angeles who was brought to Keck Hospital of USC for emergency care for an ascending aortic dissection.

The patient’s aortic dissection had caused malperfusion, impeding blood flow to the legs and intestines. Fortunately — and in an approach that’s still considered unique in the medical community — the cardiac and vascular specialists at the USC Cardiac and Vascular Institute always work together from the start to develop a patient’s care plan.

Once the physicians were alerted that the patient was being referred and transported from Los Angeles General Medical Center to Keck Hospital, Dr. Han and cardiothoracic surgeon Sanjeet G. Patel, MD, PhD, began ideating treatment options together.

Patel suggested that the team try using a stent-supported cuff developed by a company called Artivion Inc. Conventionally, when surgeons repair an aortic dissection, they replace the torn section of the aortic wall with a prosthetic graft. The graft alone does not, however, address the malperfusion problem that some patients still face due to an intimal flap in the artery. The stent-support cuff helps because, in addition to providing a graft, its built-in stent supports the aortic wall, keeping it dilated to let blood flow through and ultimately aiding aortic remodeling.

Patel performed open-heart surgery to install the device. “Sure enough,” he says, “it got the blood to flow back to the patient’s legs.”

“Having access to new technologies and relationships with medical industry allows us to provide new and potentially life-saving technology,” adds USC Cardiac and Vascular Institute cardiothoracic surgeon Fernando Fleischman, MD.

Partners in successful outcomes

Malperfusion after aortic dissection requires a team to fix. Patel and Han describe how, throughout the course of treatment, their teams worked together to tackle complications.

For instance, while the prosthetic was being sewn into place, the physicians had to temporarily stop blood flow to the rest of the patient’s body. “You can imagine how stopping blood flow to the entire body could have severe ramifications,” says Patel. “Doing this requires the expertise of our entire group.”

In addition, once the prosthetic was successfully in place and blood was flowing back to the patient’s legs, his legs began to swell in a life-threatening manner. Han, who says this can happen after blood flow is reestablished, performed a fasciotomy to relieve the pressure.

Both Patel and Han point out that Keck Medicine’s expertise in handling a high volume of aortic dissection cases is why their team is routinely sent these patients to treat. Although aortic dissection is a rare disease, the USC Cardiac and Vascular Institute treats nearly a case every week. As a result, the team — from surgeons and nurses to ICU intensivists and anesthesiologists — knows how to anticipate what could go wrong based on past experience.

Today, the patient is doing well. The team continues to monitor his status with routine CT scans, which aortic dissection patients usually undergo for the rest of their lives to keep an eye on whether further treatment, like remodeling the aorta, is necessary. “He’s doing great,” Patel says. “I saw him by telemedicine two weeks ago. He’s back to his normal life.”

Research creates hope for aortic dissection patients

What makes an aortic dissection particularly dire is that leading up to it, patients are often asymptomatic. For instance, the male patient in this case had no prior symptoms.

“People who have an aortic aneurysm, or a dilated aorta, are more at risk, but you generally don’t know if you have that,” Patel says. Sometimes, the condition remains dormant. “If you don’t have any symptoms, very rarely will the aneurysm get big enough to start compressing other structures.”

Approximately 5% of people who develop aortic dissection may have a genetic-based syndrome such as Marfan syndrome or Loeys-Dietz syndrome. “But the majority of people, the other 95%, don’t,” Patel says. Older patients who have high blood pressure or end-stage renal disease with uncontrollable hypertension may also be at risk.

“Most other people,” he continues, “wouldn’t even know that they are harboring the propensity of developing an aortic aneurysm or an aortic dissection.”

Patel and his team are now doing preclinical research to identify markers that could help them screen at-risk patients. “This is a new frontier in aortic dissection — trying to understand how it happens in the other 95%,” Patel says. “Right now, when we sequence people’s DNA to determine their genetic risk, for instance, we can’t find known genes. There’s a lot more we need to know.”

USC Cardiac and Vascular Institute

The USC Cardiac and Vascular Institute provides noninvasive treatments and specialized surgical therapies for conditions such as aortic aneurysm, congenital heart disease, heart attack, heart failure, stroke and vascular disease. Our experts work together to use state-of-the-art diagnostic tools to find the root cause and identify the appropriate therapies to treat and manage your cardiac or vascular condition.

Topics